During the mid-90s, there was a curious period of time during which home computers were becoming more and more common, but the internet was still in the early stages of mass adoption. More school-age kids had computers in their home than ever, and we were using them to write up papers and do research. But Wikipedia didn’t launch until 2001, so when we were looking up facts on Greek mythology or the War of 1812, we turned to CD-ROM encyclopedias like Microsoft Encarta, which were frequently bundled with PCs. Encarta in particular wasn’t just encyclopedia software, though — it came with a game called MindMaze.

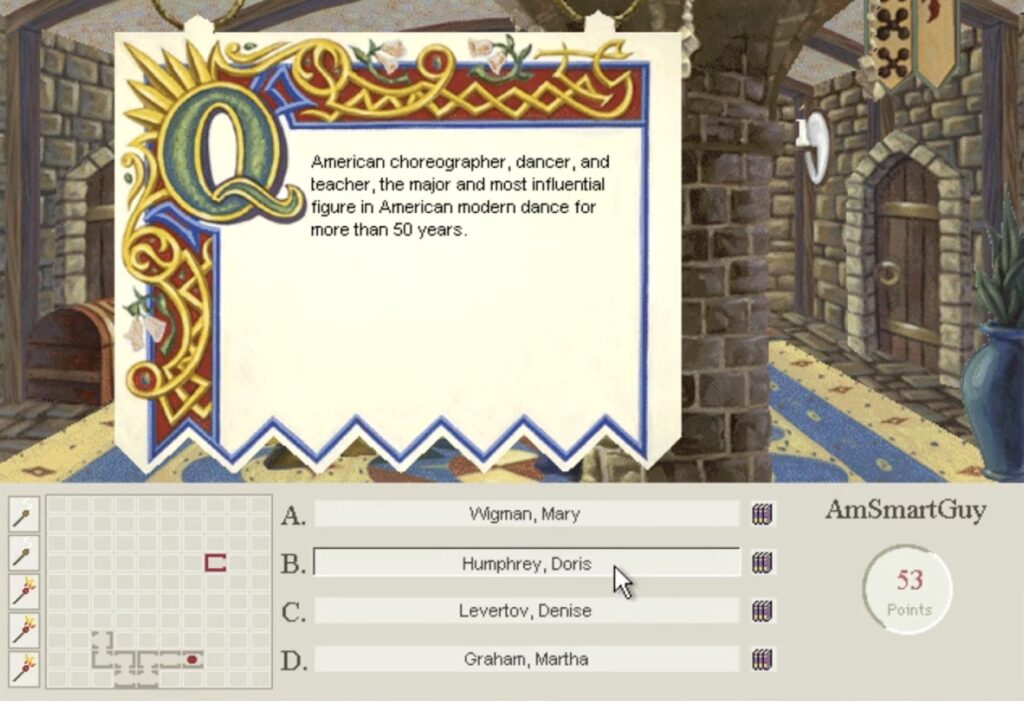

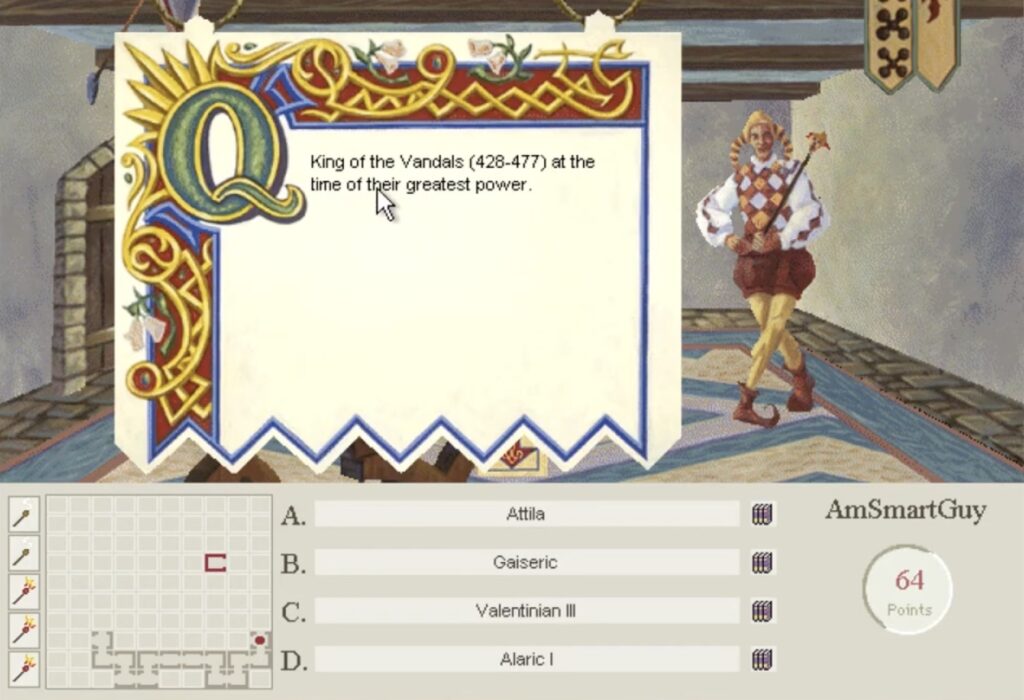

A fairly straightforward trivia game, MindMaze didn’t really need any kind of premise or even to exist in the first place, but its designers went above and beyond. Players travel back in time to the castle of King Miser the First, where they must break a curse by traversing the floors of the castle and answering trivia questions to open doors. While exploring the castle, the player can speak to various characters and click on paintings that lead to Encarta articles. Additionally, each question presents links to relevant articles, meaning that it isn’t just about memorization — MindMaze encouraged you to dive into Encarta’s pages and dig up the answers to its queries.

MindMaze was included with versions of Encarta from 1994 to 2007, though I mostly played the version from Encarta ’95, which we received along with a lot of other software designed to show off the “multimedia” capabilities of our first family computer. I’m not sure if it actually taught me anything historical, but that wasn’t really the point — the game, and interactive encyclopedias like Encarta, opened up new ways of thinking about and interacting with knowledge.

Today, we take for granted that we can hit up Wikipedia on our phones, skim an article, and maybe even pull up a video or audio clip on a subject. Back then, it seemed magical to be able to have this kind of power. You have to remember, this was the dark ages. All we’d had up until that point when it came to research for schoolwork was big leather bound encyclopedias. Being able to click around an interactive encyclopedia felt futuristic and cool.

To me, MindMaze seemed like magic. But behind the scenes, things were a little more complicated. According to an interview with Amy Raby, who was Development Manager of the Encarta team at Microsoft, the original development of MindMaze was contracted out while the internal team was working on the main Encarta software. Apparently, this led to some serious performance problems: “The original version was written, I believe, in Visual Basic or some other interpreted language. It had performance problems. All the rest of Encarta was written in C++, with some small portions written in assembly to make them a little extra zippy.”

The development team wasn’t happy with MindMaze’s performance, but they weren’t the only ones. Bill Gates himself apparently tried it out and emailed the team, claiming that “this is the slowest thing I have ever seen!!” Gates’ dissatisfaction, however, was music to the team’s ears — it meant that they would be able to fix it in the next version, and they

did. MindMaze was once again contracted out, but this time it was rewritten in another language with better performance.

I had no inkling of any of this as a kid — all I knew was that our new computer let me play a medieval trivia game that blew things like Mario is Missing out of the water. MindMaze didn’t try to hide what it was or make the medicine of learning go down smoother with some cheap platforming gameplay sections. And as a result of that, I remember it a lot more fondly than most “edutainment” games of the time.

Leave a Reply