In the 90s, there was no Twitter, no Discord, no social media of any kind. What we did have were real-time chat rooms and programs. These were mostly text-based, with a few notable exceptions — and one of those was The Palace.

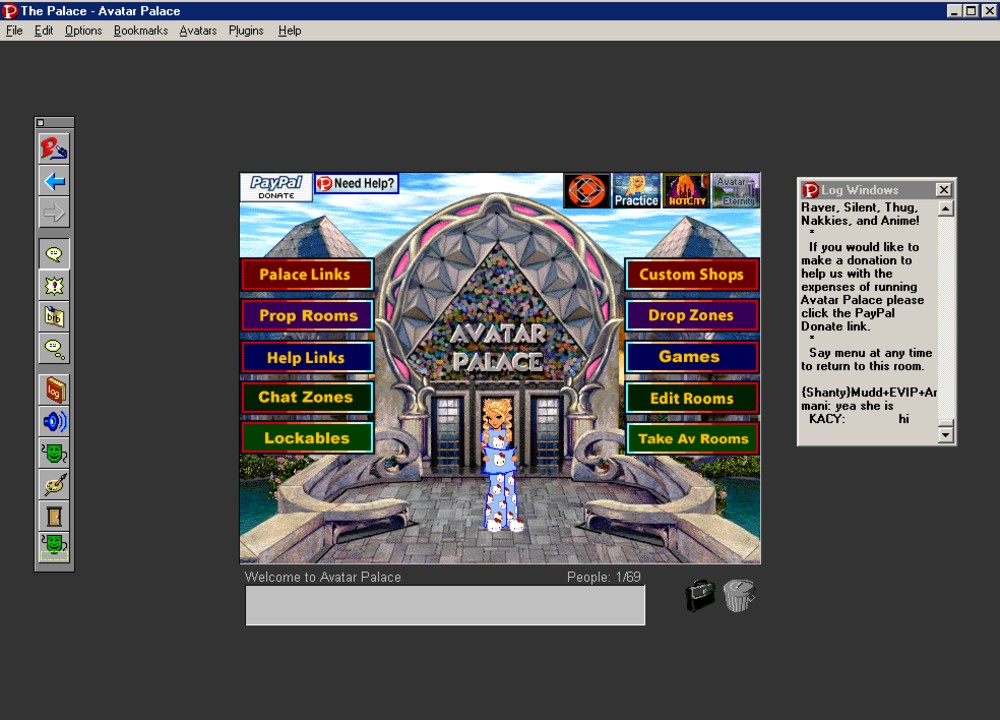

Created by Jim Bumgardner and produced by Time Warner Interactive in 1994, The Palace was released to the public in 1995, and it completely changed my perception of the internet. It presented a series of servers (or “palaces”) in which you could interact with strangers using a graphical interface, explore different rooms, and even play games.

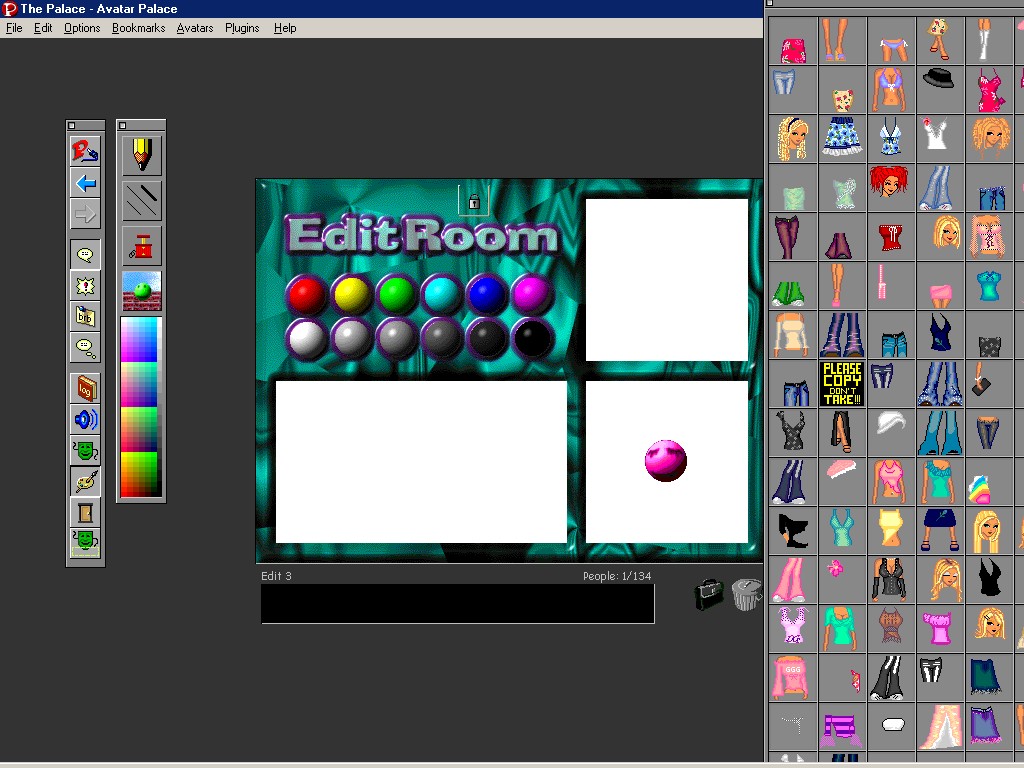

The default Palace avatar was a bright yellow smiley face. You could dress your avatar up with up to nine bitmap props included with the software, like a hat or an eyepatch. But users discovered pretty quickly that the props system wasn’t limited to adorning the friendly orb everyone started out as. By editing bitmaps, you could essentially create any avatar you wanted. And so, avatar customization became a major draw of The Palace.

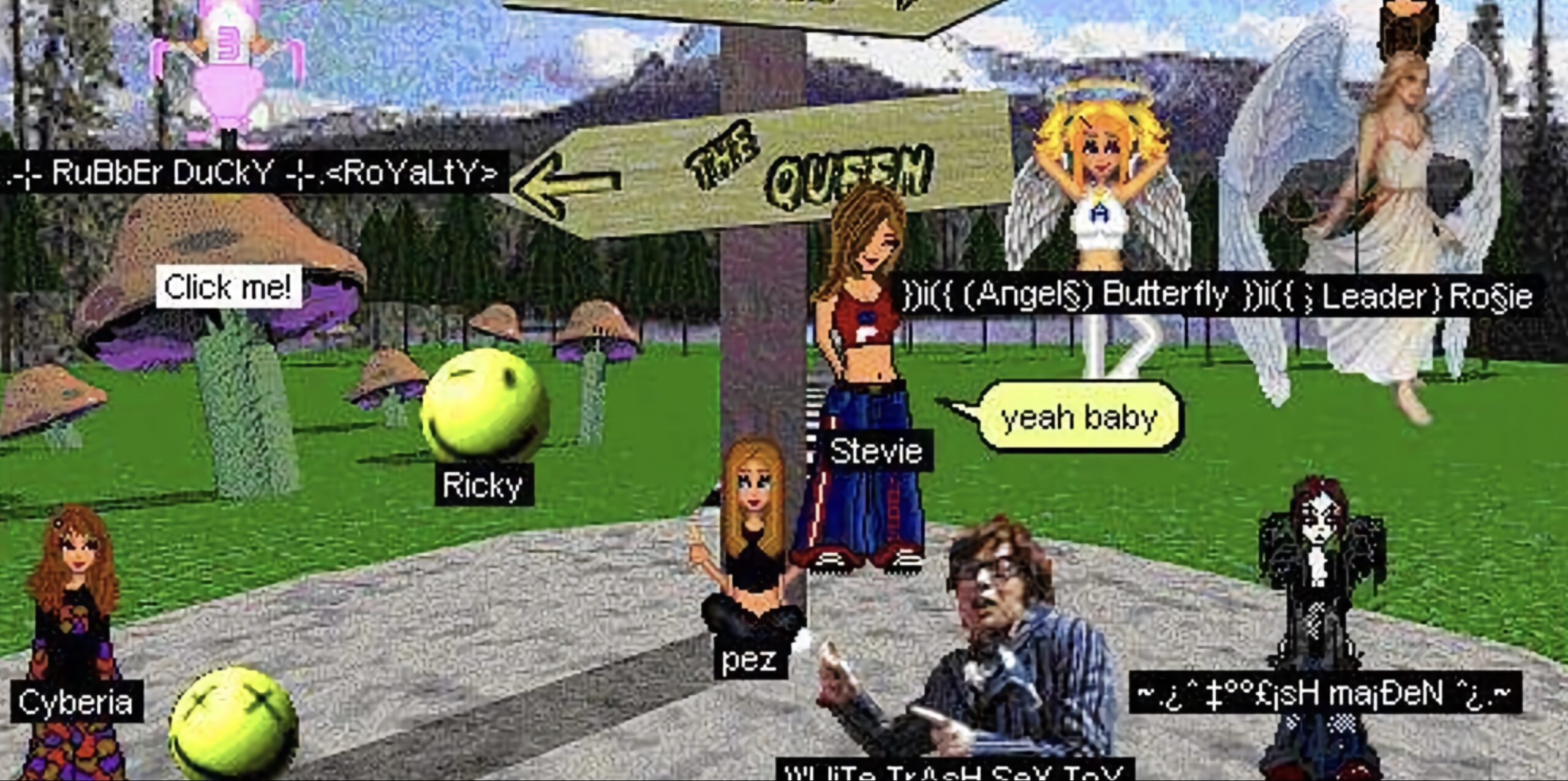

Those 2000s-era Dollz, Sk8ters, and Preps sprites you might still occasionally see floating around? Those blew up on The Palace — they became the go-to look for cool kids, allowing for experimentation with different colors and styles within a standard paper doll format. But they weren’t the only popular choice.

Users on anime and gaming-themed Palaces like Balamb Garden and Ship of Fools frequently employed sprites ripped from 8- and 16-bit video games, which were beginning to become freely accessible online via emulation. Software like ZSNES let players disable different layers of the screen to isolate a character, drop it into Paint (or Photoshop if you were lucky and/or rich), and import it into The Palace. Suddenly you could be Link, Mega Man, or Goku, or even an original character based on them if you had the editing chops. And it didn’t stop there.

In addition to manually loading in your avatar one block at a time, The Palace let you save looks to hotkeys. And someone, somewhere got the idea to use this function to simulate the anime battles of shows like Dragon Ball. Sprite battles required at least three participants — two players and a judge — though they frequently gathered crowds of onlookers.

When the judge said “fight,” the players would click around the room, rapidly shifting between sprites of their avatar punching and kicking their opponent. Once the judge had had enough, they declared “charge,” which was the players’ cue to switch to sprites of their character powering up for a final attack. Then, the judge would say “release,” and each player attempted to tag their opponent with a massive laser or fireball. Whoever hit first — in the judges’ eyes — won.

Sprite battling wasn’t very sophisticated as a game, and basically boiled down to the fastest clicker during the “release” phase. But it was an elaborate social occasion that provided users an opportunity to demonstrate their artistic abilities. Sprite editing — the alteration of game art to create new characters — was an in-demand skill, and those who were particularly creative were practically revered. In retrospect, it was pretty amateurish stuff for the most part — “pillow shading” was regarded as a sophisticated technique — but that was kind of the point.

These were early online fan communities interacting with strangers in real time, appropriating corporate imagery via illicit means and mashing it together with the aesthetics that were popular at the time — hip hop, anime, and nu metal. (Korn’s launching of an official Palace definitely contributed to the program’s success in a major way.) It was messy, it was crass, and today you might even call it cringe, but it was a lot of fun.

Server owners built games into their Palaces, too. The aforementioned Balamb Garden, as you might expect, featured several Final Fantasy-themed games, including the popular card-based minigame Triple Triad from the then-new release Final Fantasy VIII. I never played FFVIII, but I sure played a lot of Triple Triad on The Palace.

But of course, the internet at the turn of the millennium was a chaotic and rapidly changing place. The Palace was shuffled around between various buyers during the early 2000s, and official development on the software eventually ended. Along with the notion of real-time chat rooms generally speaking, it was mostly supplanted by nascent social networking sites like MySpace and Twitter, which eventually evolved into social media. However, the program’s original site, thepalace.com, is now owned by a user who maintains listings of active Palaces — the Korn Korner is even one of them.

The Palace was a magical part of my personal internet history, as well as seemingly a lot of other people’s. At The Outline, Nicole Carpenter wrote about how The Palace was a place to experiment with fashion and style. On Twitter, Calvin Stowell posted about how the first person he ever came out to was a friend on Balamb Garden. I wouldn’t be surprised if many users had similar experiences. Whether The Palace helped you play with presentation, learn new skills for interacting with the digital world, or simply relax and have fun with your online friends, it was something special — and if you were there, you know.

Leave a Reply