A version of this piece originally appeared at ZEAL in 2017.

It is the mid-90s and you are at the video store on a Friday night, the air swirling with the smells of buttered popcorn and plastic VHS cases. CRT screens suspended from the ceiling play one of the latest releases, the list of titles enumerated on a black and white plastic letterboard mounted above the registers. Eye the Twizzlers, the Junior Mints, the gumball machine that promises a free rental to anyone who receives a black ball from its unseen depths. Zoom past the seemingly endless racks of movies to the back of the store to the games section.

Now you have to make a decision. Faced with a wall of boxes depicting strange characters and emblazoned with outlandish titles, you have to decide: which will be your companion for the weekend? You have to choose carefully, because pick wrong — a game that’s too difficult, too boring — and that’s the next three days gone. But maybe this time you get lucky, and you stumble across a game sporting a cover looking straight out of a Saturday morning cartoon — a cover which was actually redesigned for American audiences, turning the hero from a smiling youth into a musclebound, rampaging Conan figure. But you don’t know any of that, not right now. All you know is what you’ve gleaned from the tiny screenshots and selling points listed on the back of the box (“New perspective and larger animations for incredible graphics!”)

It is the mid-90s, and you are going home from the video store with Breath of Fire II.

A Sword Has a Long Blade

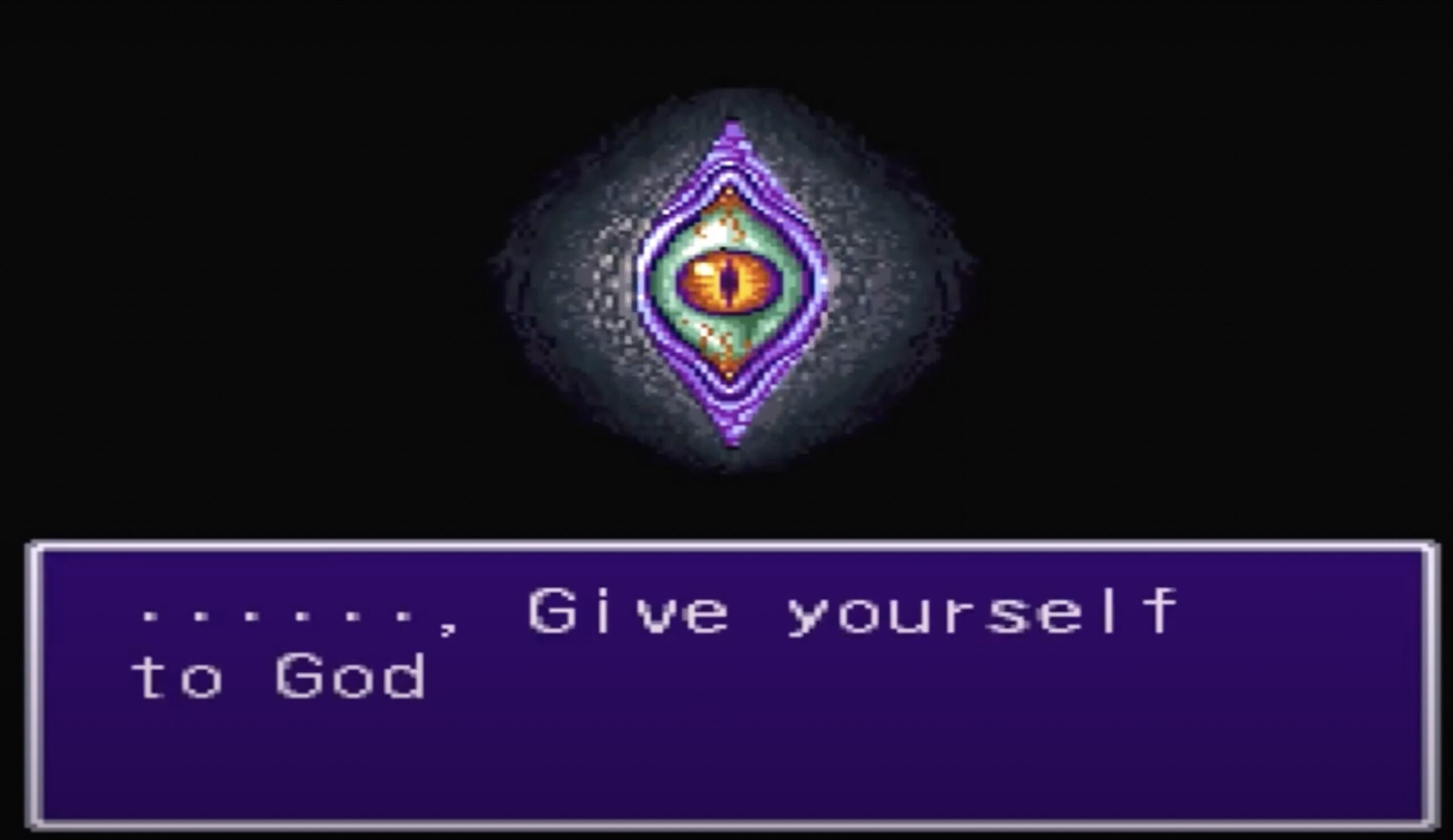

Breath of Fire II is a Japanese roleplaying game for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System in which the player takes on the role of Ryu, a blue-haired kid with a familial connection to dragons. When first beginning a new game, the player is first treated to a terrifying opening in which a single, piercing eye demands, “give yourself to God.” As the game world appears for the first time, it is rendered in black and white, echoing the opening of The Wizard of Oz. Like Dorothy, Ryu ends up far from home — except that rather than being transported to a colorful world of magical creatures, six year-old Ryu one day finds that everything he’s known in his short little life has been replaced by something unfamiliar and vaguely sinister. His family is missing and nobody remembers him. Taken in by a kindly priest, he meets an anthropomorphic dog and they run away together to the big city, creating a new life for themselves as freelance problem solvers.

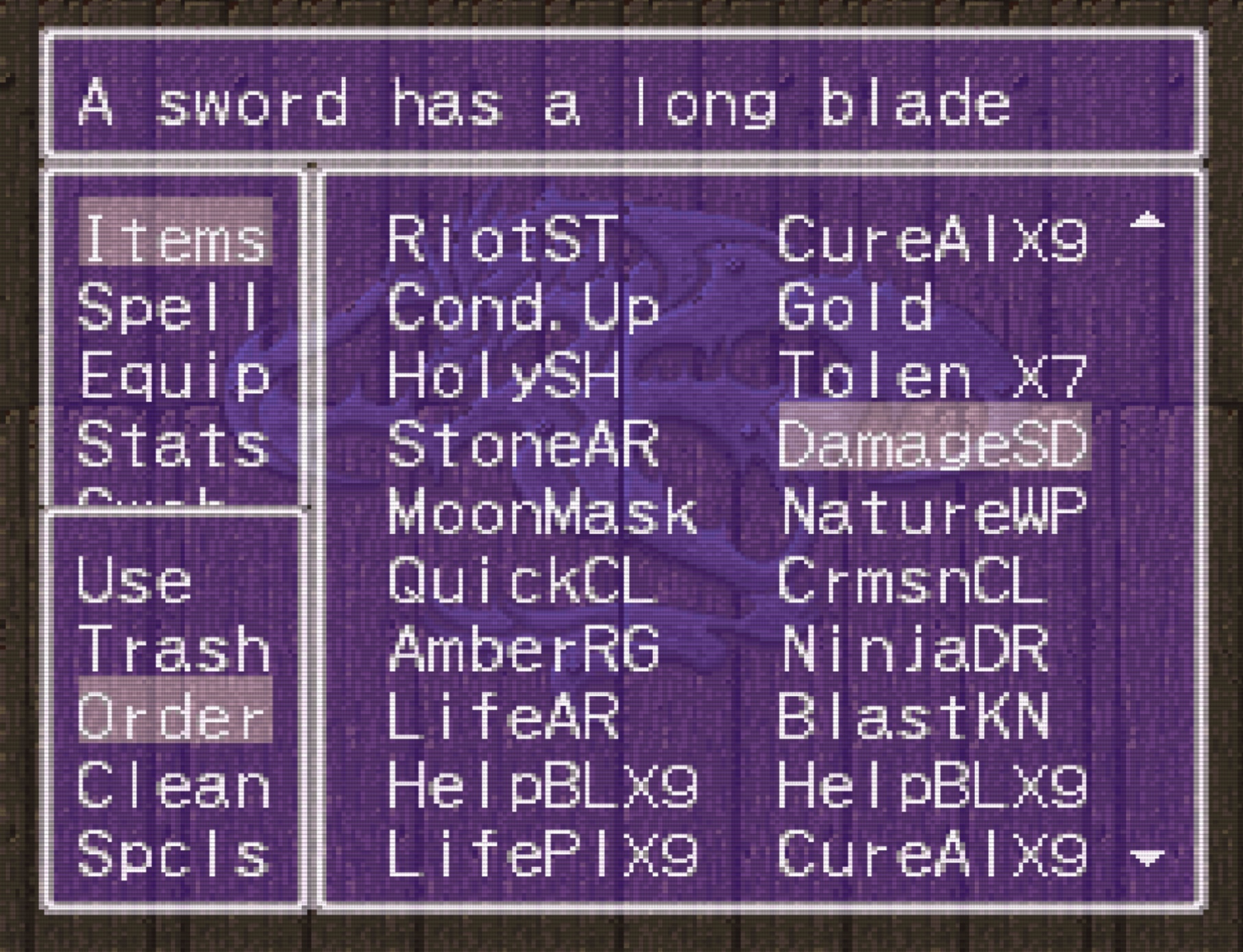

In the course of the game, Ryu travels the world and gradually unravels the mystery of what’s happened to it and his family. In doing so, he acquires allies ranging from a frog man to a sentient plant, explores the insides of a giant whale, and turns an entire town into a giant airship. Breath of Fire II is a long game, as well as an inscrutable one for most English-speaking players who encountered it in its original release — translation errors abound, as do awkward shortenings of romanized names to fit within text boxes originally designed for Japanese characters. A wooden staff becomes “TreeST”, a vitamin becomes “HelpBL.”

The nature of this kind of game is that by the time the ending rolls around, the world looks much different than it did when the player started out. Many of most popular games at the time, typically platformers, weren’t like this — sure, a character like Mario explores different areas as he progresses, but he doesn’t fundamentally change as the game goes on. When Breath of Fire II ends, characters might look completely different than they did when you first encountered them, which might not even have been until halfway through the game.

Of course, many players — especially those who took the game home only for a weekend — would not have rolled credits on it. The combination of confusing text, difficult combat encounters that require grinding to build characters’ skills, and a sprawling world mean that Breath of Fire II takes dozens of hours to complete, a feat beyond many children’s abilities. But if you did rent the game, you might have been prompted not just to start a new adventure upon starting it up, but to continue an existing one. Opening one of those other files would drop you into the middle of the story with no recap and no explanation of what was happening — unless some fastidious player had scrawled something in the ubiquitous “notes” section at the end of the instruction manual.

The world a stranger might leave you could be utterly unrecognizable to someone just starting out. It might be populated with unfamiliar characters, who might be waiting in an unfamiliar location to complete some unfamiliar quest. Whereas an early player might have been facing small, nonthreatening monsters, this world might be full of terrifying foes. Entering a world like this, what would you feel? Would you think of yourself as a trespasser on the ground of another’s accomplishments? Or would you wonder at the sights — underwater palaces, flying cities, caverns full of demons — you might never be able to see on your own?

The Medium of the Cartridge

My sister texted me the other day to tell me that the video store we visited nearly every weekend as kids had finally folded, replaced with a vape shop. How it made it to 2017 I’m not sure — the other rental place that we’d frequented in our childhood, a sprawling regional chain store that provided free popcorn called Jumbo Video closed over a decade ago.

Select Video was a part of my childhood, and I’ll probably always feel there’s something magical about the space of a video store. But beyond the purely nostalgic, the closing of this last holdout reminded me of an experience that was particular to a time and place, owing to a convergence between the technological and the social — going home with a game for a weekend and ending up sitting in a stranger’s world.

Video games are expensive, and this was even more true before digital distribution and Humble Bundles. The idea of a library bursting with untouched titles was completely unfathomable to me in the early 1990s. On the rare occasions that you bought a new game, you made an educated guess based on gossip, what you’d gleaned from magazines, and cover art. Sometimes you’d end up with The Rocketeer on SNES and there wasn’t much you could do about that. In an information-starved environment — before the advent of easily-accessible gameplay footage, before the existence of a diverse critical ecosystem — renting games was one of the only means we had of avoiding that kind of scenario.

And, of course, this was the era of cartridge media. One of the key differences between a cartridge and optical media is that the user’s data is stored with the game program itself in the case of the former — with the read-only medium of the CD, the user’s data is saved via memory card or hard drive. Few players deleted their save data before returning a game — there was no norm in place in the same way that there was an urging for viewers to be kind and rewind their VHS tapes. Besides, games which supported battery back-ups had no standard means of erasing their saved data. So even if players wanted to wipe their saves before returning a game, they might not have known how.

What this meant is that each copy of a game at a video store might carry a stranger’s save data. It might carry multiple, if it supported more than one save file. A single file might even represent the cumulative efforts of many people building on the same file, unbeknownst to one another. Unlike a film or, later, a CD-based game, where previous viewings don’t change the media itself — beyond, perhaps, gradually wearing it down — players could change the experience of a cartridge based game for those to come.

Load up save file 3, the one that doesn’t belong to you. Ryu, the scrappy protagonist, now transforms into a dragon to do battle against enormous devils. You traverse the world atop a giant bird. The empty town you start to rebuild early on in the game is full of people, including “shamans” who will fuse themselves with your party members — turning, say, Bow, your childhood dog friend, into a powerful robot with a gun for an arm. Everything’s different, unrecognizable. Amazing, but perhaps a little frightening.

How many hands did that save file pass through? Maybe it was the work of one person, coming back to the same cartridge over and over. More likely, it was picked up and carried on by kids whose time with a game this size would never be enough to finish it solo. A distributed effort, ephemeral connections shared through chance encounters with a cartridge and paper manual circulating through a city, continuing until the title fell out of favor, the file got wiped, or the video store finally closed for good.

I don’t mean to romanticize these experiences, nor to suggest that they’re entirely gone. You can still buy a Pokémon cartridge and discover a stranger’s old friends, assuming the battery these older games save to hasn’t failed yet. And some designers have explicitly attempted to convey a kind of relay experience through experiments like Chain World. For the most part, though, stumbling into another player’s world isn’t something that happens anymore. Partly that’s because our “copies” of games have become representational, independent bundles of data, rather than physical items circulating in an ecosystem. But the experience was dead long before downloads — the advent of optical media meant that we began keeping our virtual worlds separately from the logs of our journeys within them.

Memory Loss

I didn’t finish Breath of Fire II until years after I first encountered it, when I was able to play it on an emulator with access to save states. In the interim, ROMs had become relatively easy to find, but we still passed around links to rare ones like precious secrets. Downloading the game probably took me upwards of a half-hour on my family’s precarious dial-up connection.

That sense of rarity has all but evaporated now. Is that good because it increases our access to older games? Bad because it cheapens those experiences? It’s too easy to come to pat conclusions about access to media like this. What I know is that changes in formats and information environments don’t just change our ability to play games, they change our experience of them.

Of course, there will always be mysteries. Some of the screenshots for this essay were obtained using downloadable save files that drop you at the end of the game. Those files were themselves nearly ten years old when I downloaded them. Who posted them? Who is “GDN,” the name of the hero character? I’ll never know, just like I’ll never know who built the virtual town I visited twenty years ago. All I can do is wonder, and feel an ethereal sense of kinship with the travelers who have wandered through these worlds before me.

Leave a Reply